Reducing Turnover and Increasing Job Satisfaction in Food Services

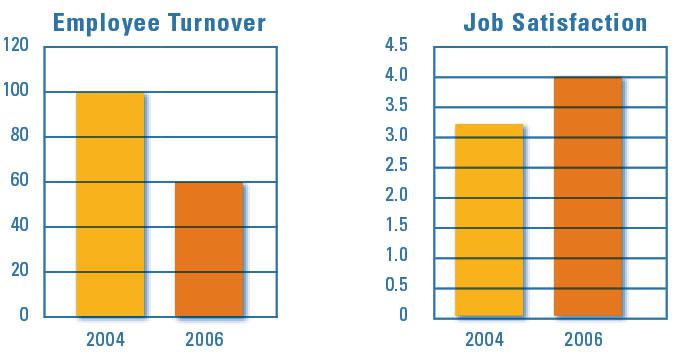

The year was 2004, and it wasn’t pretty. According to the results of our “employee climate survey” in Port Townsend, Wash., The Food Co-op’s food services team had one of the lowest levels of job satisfaction in the organization. The numbers told the story: employee turnover was a devastating 100 percent, and the team was functioning at a break-even point, with margin minus labor a paltry 2.2 percent. Managers breezed in and out of the department, with no fewer than eight managers in four years, and employee performance issues were rampant.

Victoria Wideman knew a challenge when she saw it. She stepped up to head the team in August of 2004 and began making fundamental changes. “I knew if we didn’t get it together, there wouldn’t be a deli.”

Without an iota of food service or supervisory experience, Wideman was an unlikely candidate for such a challenge. And let’s be honest: at first glance, her military service in the United States Army didn’t exactly spell “Great fit!” in our cooperative culture. Yet this is a story of how her life experiences and leadership skills ultimately fit the bill more than any “foodie” who had come before her.

Under Wideman’s leadership, our co-op’s food services team underwent a transformation. The results of the 2006 employee climate survey show the food services team scoring above the organizational average in every topic, most notably in job satisfaction and overall management practices—and employee turnover is down by 35 percent.

What steps did Wideman take to send the job satisfaction of her team soaring?

Wideman: I believe that the sum of my life experiences prepared me to work effectively as a manager. I understand the meaning of team work and how to pay attention to detail. In the United States Army during the late 1970s and early ’80s it was imperative that each company, platoon and squad work together to accomplish its military objective.

Whether we were climbing a wall on the obstacle course or on a 20-mile military maneuver through the woods, our mission was to have every soldier come out on the other side. This could only happen with team support. If I was having trouble clearing the wall, my teammates would give me support by saying, “Come on, you can do it, come on, come on.” And with that constant encouragement and team effort, each one would eventually clear the wall and continue on to the next challenge. I used this team-building technique while turning around the food services team. When a teammate says, “I can’t do it,” or “Why should I have to do it?” I reply, “Because you’re part of this team and it takes all of us to make things happen.”

Paying attention to detail is another trait that has worked with team building. In the beginning nothing is too small to address. In the Army it was mandatory that our boots maintain a constant shine. The only way to obtain this objective was to spit shine the boots. It seemed like such a small, meaningless task but the payoff was remarkable. I was always ready for inspection and proud of the fact that I had taken the time and effort needed to get the shine on the boots. Not only did paying attention help me personally, it also had an impact on the entire team. While individually we were held accountable for our uniforms, as a team we were also held accountable for the way we looked in formation.

Hake: How would you describe your team before you assumed oversight?

Wideman: Dysfunctional—there were few systems, few boundaries, and few guidelines that were being followed.

Hake: How would you describe the team now?

Wideman: We’ve built a foundation of trust. We don’t settle for mediocrity anymore.

Hake: What are the most important changes you made to raise morale and create a real team?

Wideman: The first thing I did was officially make us “one” by renaming the team “food services” instead of “kitchen” and “deli.” I then began meeting with each team member individually, letting each one know that everything they do is important; every job plays a necessary role in the success of the team. I told them that we needed to turn the department around. I told them I couldn’t do it by myself, and I asked for their support and used a different style to communicate this message to each team member.

The next thing I did was to gain agreement on systems and guidelines. Once this was accomplished, we began holding each other accountable for using these systems and guidelines. I started focusing on each team member’s strengths and making sure that I was giving them the tools needed to perform the jobs.

Hake: Books about teamwork and performance management abound; were there any books in particular you found useful?

Wideman: Our general manager, Briar Kolp, recommended, First, Break All The Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers do Differently (1999). The authors, Buckingham and Coffman, validated my approach of getting to know team members to build on their strengths rather than trying to fix their weaknesses. The book provides guidance on setting performance expectations and defining performance outcomes. The authors provide a set of 12 questions that measure the key ingredients necessary to keep the best employees. I used this tool to assess how team members were feeling about their jobs.

Hake: What sort of resistance did you face from team members and how did you manage their resistance?

Wideman: I was honest with them. I told them if we didn’t make some changes there might not be a food services team. There were times when even the most basic expectations, like arriving to work on time, were not being met. When this happened, I would reiterate the expectations and standard. I would say, “Here’s what I need…” and then ask, “Are you willing and able to make the changes necessary to be successful in your job, and to work at the level that is needed and expected?” When they say, “I can’t,” I first ask why, and then give them solutions/ideas on how they can achieve the goal, while continuing to hold them accountable for the job they signed up to do. I see their potential, they know what’s expected, and I hold them accountable.

Hake: How did your team move from breaking even to contributing to overall store profit?

Wideman: Several changes were made. We brought new talent and experience to the team and created tighter inventory controls. For example, we began using receiving logs and recording transfers to prepared foods.

Hake: What did you try that didn’t work?

Wideman: I made the same mistake that many new supervisors make when trying to get to know their team members. It’s a balancing act; a manager is not there to make friends or carry her staff’s burdens.

Hake: What do you know now that you wish you would’ve known at the beginning of this journey?

Wideman: Leading people can be difficult. It is a continuous process that takes patience, time, and commitment.

Hake: As you look at the transformation of your team, what are you proudest of?

Wideman: The mutual respect that comes from being seen as an equal. I used to spend so much time managing the poor performers, and now I’m spending my time mentoring and instilling pride in the good performers.

***

Reducing Turnover and Increasing

Job Satisfaction: What Worked

Hiring

A structured, multi-step interview process, including reference checking. No more hiring on the fly.

Performance Management

Address performance concerns immediately. Wideman advises, “In the beginning, no issue is too small to address.” After gaining agreement on important procedural changes, it’s important to follow through and hold one another accountable for the agreed upon behavior.

Performance Reviews

Conduct reviews on time. Monitor and measure performance all year long to provide thorough, meaningful feedback. Doing so lets staff know you care about their growth and development.

Team Meetings

Provide mini coaching sessions before the meetings to help staff develop the diplomatic communication skills needed to express their requests of other team members.

Training

Don’t assume team members know the basics. Wideman developed a 70-question assessment to identify training gaps. The assessment created a springboard for clarification that ultimately resulted in consistent work practices. She knew her team had rounded the corner when she had her staff take the assessment again nine months later, and they were on the same page.

***

Robin Hake is human resources manager at The Food Co-op in Port Townsend, Washington ([email protected]).